Squire Patton Boggs | Francesco Liberatore | Gorka Navea | Bartolomé Martín

European Union

The EU Data Act (Data Act) entered into full effect earlier this year, but case law is yet to emerge to provide authoritative interpretation on some of its key provisions. Absent any case law on point, the chief compliance officer, chief digital officer and legal departments of companies falling within the scope of the act are at pains to devise workable compliance strategies.

The primary pain points for compliance with the Data Act include significant legal uncertainty, contractual review burden, substantial technical and operational changes, as well as potential business model disruption. In practice, this means that organisations should already have assessed which products and services fall within scope, identified the relevant data and data flows, reviewed their contractual landscape and considered the operational impact of the new access, sharing and switching obligations.

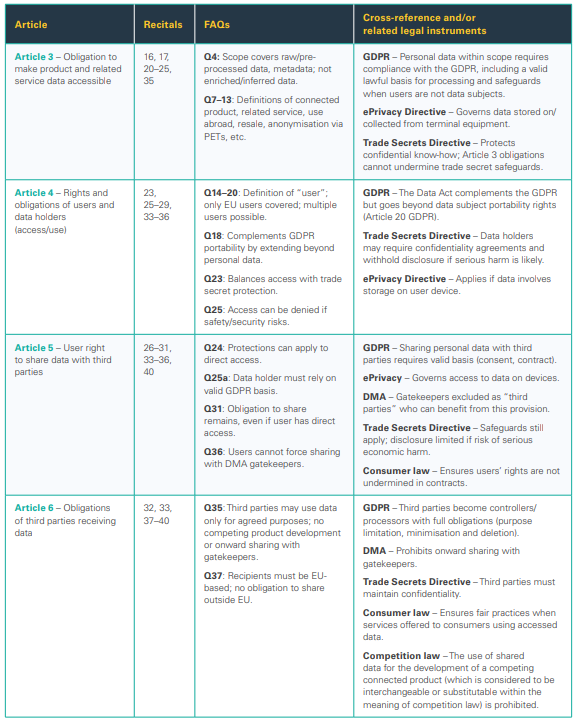

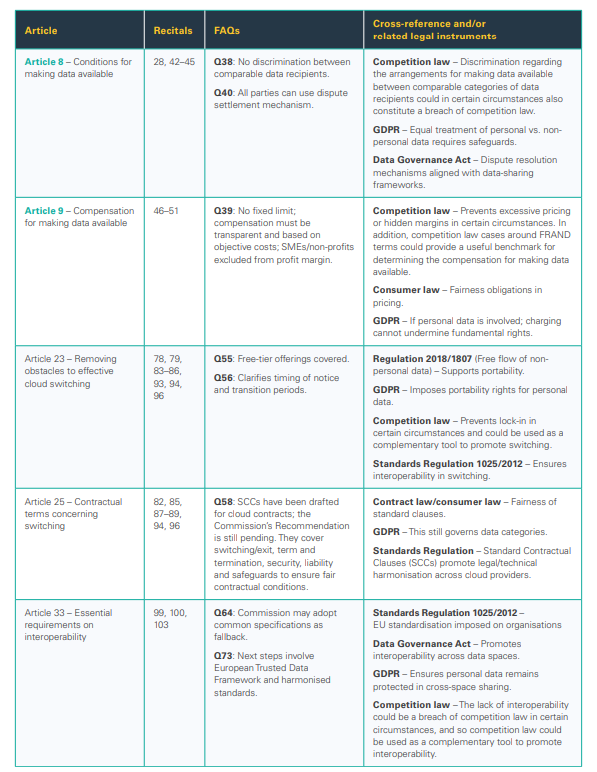

This client alert tries to assuage some of these pain points by providing an overview of the act (Section A), its key practical compliance challenges (Section B) and a correlation table between each of the provisions of the act and its recitals, the unofficial guidance provided by the European Commission in its FAQs document and other overlapping statutory instruments (Section C).

We can assist clients with every step of the compliance journey, including:

• Initial assessments of the Data Act’s application, identifying which products and services fall in scope • Mapping data flows and assessing which datasets are in scope

• Developing a priority-focused, structured and business-aligned approach to compliance

• Contractual reviews of B2B agreements, user terms and conditions, and incorporation of the standard contractual clauses for cloud switching and interoperability

• Assessing interplay and compliance with other related laws

For example, companies that operate in the cloud servicing sector will likely need to make an effort to understand the types of information they need to make available, consider how to amend their terms and conditions to account for users’ rights to access their data and make this data available to third parties, while balancing the requirements of the Data Act to make these terms fair to users with companies’ commercial considerations.

A. Summary of the Data Act

The Data Act is one of the cornerstones of the EU’s digital strategy and a key instrument for building a fairer and more competitive data economy. Its main purpose is to ensure that the vast amount of data generated by connected products and related services can be accessed, shared and reused under fair conditions. Until now, such data often remained locked within the systems of manufacturers or service providers, limiting competition and slowing innovation. The regulation seeks to change that by giving users more control over the data they generate, creating obligations for data holders to make that data available and setting safeguards to protect competition, trade secrets, privacy and security. The ultimate aim is to rebalance relationships between the different actors in the digital ecosystem and encourage a more open, contestable and transparent use of data across the EU.

Status and Enforcement

After its formal adoption in June 2023, the Data Act entered into force on 11 January 2024. Most of its provisions started applying on 12 September 2025, giving organisations time to adapt their technical and contractual frameworks. As a regulation, it is directly applicable across all EU member states, ensuring a uniform legal framework for data access, sharing and use. It also interacts closely with other key instruments, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the ePrivacy Directive, the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the Trade Secrets Directive and EU competition law, forming part of a broader legislative ecosystem that governs the European data economy.

In terms of enforcement, the Data Act follows a decentralised model similar to that of the GDPR: member states are responsible for designating competent authorities and establishing effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties for infringements. This approach allows flexibility at the national level, while maintaining a high and consistent standard of protection and compliance across the EU.

Access and Use of Data (Articles 3–6)

A key feature of the Data Act is the creation of a fair framework for accessing and using data generated by connected products and related services. It grants users the right to obtain and use the data they generate, ensuring that access and sharing take place under transparent and non-discriminatory conditions. This obligation mainly concerns raw and pre-processed data, and excludes enriched or inferred data derived from further analysis.

The Data Act seeks to balance users’ rights with the legitimate interests of data holders. Users gain control over their data, but holders may protect competition, trade secrets, confidentiality and security. These provisions go beyond the portability right under Article 20 of the GDPR, as they also cover non-personal data and mixed datasets.

Users may also request that their data be shared with third parties of their choice. Such sharing must rely on a valid GDPR basis, respect trade secret protections and exclude gatekeepers under the DMA. Third parties may use the data only for agreed purposes, and are prohibited from developing competing products or disclosing the data further.

Fairness and Compensation (Articles 8–9)

The Data Act also lays down rules on the conditions for making data available, as well as on compensation for doing so. Access must be provided on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, ensuring equal treatment among comparable data recipients. Any differentiation must be objectively justified and discriminatory arrangements could, in some cases, breach EU competition law.

As for compensation, charges must be transparent and proportionate to the actual costs incurred. Profit margins are not permitted when the recipient is a small- or medium-sized enterprise (SME) or a non-profit organisation. These provisions aim to prevent excessive pricing practices and ensure economic fairness, following the competition law principle of fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

Cloud Switching and Contractual Terms (Articles 23–25)

Another major aspect of the framework concerns the removal of barriers to switching between cloud service providers. The rules aim to prevent customer lock-in and ensure that users can move their data, applications and digital assets between providers without undue obstacles, included elevated costs. Providers must allow switching under clear and fair conditions, with reasonable notice periods and transparent transition timelines.

Contractual clauses must also reflect this principle of fairness. Standard contractual clauses have been developed to harmonise practices across the EU and apply to all service models, including Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS). These provisions complement the Free Flow of Non-Personal Data Regulation, and align with competition law objectives, promoting genuine choice and interoperability in the European cloud market.

A brief comparative digression: in the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has recently concluded its Cloud Market Investigation, looking in-depth at the same issues concerning the lack of switching and interoperability between cloud providers that led to the adoption of the Data Act. The CMA concluded that the UK cloud market is afflicted by an adverse effect on competition arising from certain features of the market, including the concentration of market power in the hands (or rather their data centres) of two main cloud providers. It recommended that the newly established CMA Digital Markets Unit considers using its newly acquired Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCCA) powers to impose regulatory obligations on those two providers, that would be aimed at creating a more contestable market and promoting switching and interoperability. It is expected that some of such new obligations, i

Interoperability and Standards (Article 33)

Interoperability is another cornerstone of the framework, ensuring that different data systems and services across the EU can communicate and work together effectively. The Data Act introduces essential requirements for interoperability within and between data spaces, allowing data to flow more easily across sectors and member states. Where harmonised standards are insufficient, the European Commission may adopt common specifications as a fallback to guarantee technical and organisational compatibility.

These measures are aligned with the Data Governance Act and the EU Standardisation Regulation, reinforcing the role of European standardisation organisations in developing trusted and interoperable data infrastructures. By promoting compatibility and common standards, the idea is that this framework will reduce market fragmentation and foster innovation across the European data economy.

B. Compliance Challenges

Legal and Contractual

• Unclear legal terms – The interpretation of key concepts like FRAND compensation is highly contentious, and likely to lead to significant litigation without clear guidance from the European Commission

• Contract review and renegotiation – Article 13’s “fairness test” for unilaterally imposed contract clauses in businessto-business (B2B) data-related agreements applies to new contracts from September 2025, and many existing longterm contracts from September 2027. This forces businesses to review and potentially renegotiate a vast number of agreements, creating a significant retroactive burden.

• Interplay with other laws – The Data Act’s complex interaction with existing regulations like the GDPR, DMA, competition law and the NIS2 Directive creates a challenging web of obligations – see Section C below.

• Protecting trade secrets – While the Data Act provides some safeguards for trade secrets, companies face a difficult balancing act between their data-sharing obligations and the need to protect sensitive, proprietary information. This is expected to be a major area for future disputes.

• Extraterritorial scope – Non-EU companies offering products or services in the EU must comply and may need to appoint a legal representative within a member state, adding an administrative layer.

Technical and Operational Challenges

• Product redesign – For manufacturers, new connected products placed on the market after September 2026 must be designed to allow users easy, direct and free access to their data “by design,” requiring significant changes to product development and IT infrastructure.

• Data identification and accessibility – Companies must develop technical solutions to identify, separate (from trade secrets) and provide data in a comprehensive, structured, commonly used and machine-readable format, which many lack the existing infrastructure to do.

• Cloud switching implementation – Providers of cloud and data processing services must remove technical, commercial and organisational barriers to switching, including facilitating data transfer within a short (30-day) transitional period. This requires significant technical assistance and can affect revenue predictability from long-term contracts.

• Ensuring data continuity – A practical challenge is ensuring data rights seamlessly transfer when a connected product is sold (e.g. from one owner to the next), often requiring complex contractual “hinge” mechanisms.

Business and Financial Challenges

• Business model disruption – Companies that previously relied on exclusive access to user data for competitive advantage or aftermarket services (like repairs) will need to fundamentally rethink and adapt their business models.

• Cost and resources – The costs associated with technical infrastructure investments, legal reviews and establishing new compliance processes (similar to the GDPR rollout) can be substantial, particularly for SMEs.

• Litigation and enforcement risks – The new user rights are expected to be a key driver of litigation, including class actions. Non-compliance can result in significant fines (similar to the GDPR) and legal action from regulators or competitors.

C. Interconnected Legal Framework

The following correlation table summarises the key provisions of the Data Act, highlighting the main obligations, relevant recitals and cross-references with the European Commission’s unofficial FAQs document and other EU instruments. It shows that compliance with the Data Act cannot be achieved in isolation, as the regulation interacts closely with several complementary frameworks, including the GDPR, the Trade Secrets Directive, the DMA, the Data Governance Act and EU competition law. Together, these instruments form a coherent legal ecosystem that governs how data is accessed, shared and protected within the European single market. This crossreference approach is essential for organisations to understand the practical overlaps and to design integrated compliance strategies.

This article first appeared on Lexology | Source